Learning any foreign language well takes an extraordinary amount of dedication and effort. For many people, they “wish” they could speak Japanese (or any other language) but in reality, they don’t want to put in the effort to actually learn it. And that’s understandable – we all have plenty of things competing for our attention and our natural tendency is to procrastinate when the benefits we expect are far out in the future (we ‘discount’ those things that don’t cause immediate pain or deliver immediate rewards). Effective, well-defined goals will help you avoid procrastination and keep you on track. Moreover, rather than just studying randomly, goals will proactively focus you on the things that matter most and accelerate your progress.

Setting SMART Goals

SMART goals are a popular framework used across numerous domains as a way to define one’s objectives in such a way as to help ensure they are attainable within a certain time frame. This approach takes generalities and guesswork out of the picture, establishes a clear timeline, and makes it easier to track progress. Each letter in the acronym stands for an attribute your goal should have when you begin.

S: Specific

What, exactly, do you want to accomplish? In which specific area do you want to improve?

Can-Do Statements

One approach popular in language learning is that of defining “can-do” statements, which describe what learners can do consistently over time. Think about the situations you want to be prepared for and the level of competence you want. Don’t just say “I want to be fluent” – that’s virtually impossible to measure as there’s no consistent, universal definition of fluency. Think about specific capabilities you want to develop.

For example, consider the following situations:

- I’m going to take a two-week vacation and I want to be able to order food, find restrooms, buy souvenirs and so on;

- I want to take a working holiday for a year, live in Tokyo and teach English to elementary school kids;

- My company is sending me as the new country manager and I’ll need to do complex negotiations with local customers.

Each of these takes a very different level of skill and commitment, but the more detail in which you can describe your objective, the easier it will be for you to judge whether you’re there or not. Each of the situations above can be broken down into a number of “can-do” statements that can form the basis of a SMART goal, e.g.

- “I can understand the Shinkansen schedule, purchase tickets and find the right platform.”

- “I can ask directions to find local attractions (or restrooms).”

- “I can read a menu at the local ramen restaurant, ask questions about the dishes and place my order.”

M: Measurable

Can you unambiguously determine whether you’ve reached your goal of not? For some goals, quantifiable targets are quite straightforward: learn X number of words; pass the JLPT; study every day for 30 minutes for a month.

Other goals, while equally valid, can be a little more ambiguous to measure, such as “have a ten minute conversation with a native speaker about my favorite hobby.” In such a case, you have to be your own judge and decide whether that conversation met your standards, e.g. did your partner understand you, were your (inevitable) mistakes few and correctable, was your vocabulary sufficient for the messages you intended to send, and so on.

Whatever the case, make sure that you (or a trusted partner) can determine if you’ve reached your objective.

A: Achievable

Every goal you set should be challenging but not impossible. As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi detailed in his seminal work “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience,” one enters a flow state (a.k.a. ‘being in the zone’) when the task at hand is just outside your capabilities, neither so easy that it is boring nor so difficult that it becomes frustrating and demotivating. Do your best to set goals that land in this “Goldilocks Zone” that enables flow.

R: Relevant

Does this goal fit your “big picture” objectives? Is it going to help you achieve the ultimate transformation or identity you desire?

For example, unless you intend to become a surgeon in Japan, I cannot imagine setting a goal to learn the names of all the internal organs. On the other hand, I enjoy cooking and talking about cooking, so learning common cooking terms, names of ingredients, utensils, etc. was perfectly relevant to my overall objective of living comfortably in Japan.

T: Time-Bound

Every goal should have a deadline that is just far enough out to give you sufficient time to accomplish it but near enough to create some pressure for you to devote time to working on it (ideally daily).

Process vs. Product Goals

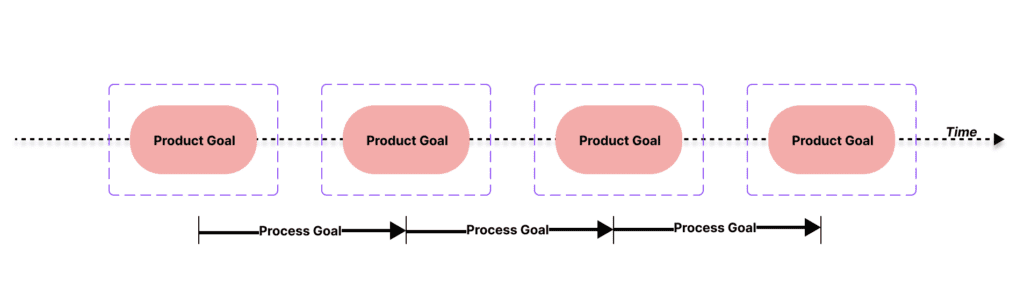

Some goals have a well-defined endpoint that can be used to assess whether you’ve reached them or not. Note that in the SMART goal formulation above, the first two letters stand for Specific and Measurable for that very reason. I call these “product goals,” as there is a final product that you’re aiming to deliver. Product goals include things like memorizing vocabulary lists or being able to read a specific news article in Japanese. You know precisely when you’re done and whether you’ve succeeded or not.

Other language-learning goals are more ambiguous. Sure, you can put milestones here and there like “Pass the JLPT N1 exam,” or “Read Minna No Nihongo Volume 1,” but day-to-day, week-to-week, those are hard things to try and put on a To Do list or calendar to track your activities.

Enter “process goals.” These are specific activities that you can schedule such as, “Study kanji flashcards for 15 minutes.” By putting process goals into your daily plan, you give yourself specific, concrete things to work on that when repeated over the long term will march you steadily toward your overall objective. For example, one of the process goals I use frequently is to spend at least 15 minutes each morning reading from whatever resource I’m principally using for comprehensible input.

I recommend you set product goals for the overall mid-term and long-term targets you’re aiming for and select the process goals that, if carried out over a period of time, make the product goals inevitable.

For example, you might set a product goal of being able to sustain a ten-minute long conversation about your favorite hobbies with a tutor or language exchange partner. Then you can set daily process goals such as “review vocabulary related to my hobby for ten minutes each day for one month,” and “Spend five minutes shadowing a YouTube video about my hobby in Japanese each day for one month,” and so on. Consistent execution of the process goals over time will deliver your product goal.

The illustration above shows how you might sequence a number of Product Goals to achieve over time and how you use appropriate Process Goals to reach them.

Psychological Trickery

Many years ago, I used to routinely psyche myself out of all sorts of goal setting for fear of “setting the wrong goal.” Who wants to devote oneself to grandiose, long-term goal planning when the outcome isn’t assured and the opportunity costs could be quite high? The resulting “paralysis by analysis” really killed my personal productivity.

Now I reframe it as defining “projects” that are entirely equivalent to Product Goals, minus the mental baggage I accumulated in my 20’s and 30’s. “Projects” are a nice way to look at things because they are typically shorter-term (I like 90 days as a default) with fixed start and end points. At the end of the project, I hold a little retrospective to see what worked well and what I’d change, then launch into the next one.

Your Move

Start out by defining just one Product Goal (or Project) that you can complete in 90 days, then identify the daily Process Goals that will get you there. Write them down, review them every day, identify when and where you’ll work on them and block of time on your calendar if appropriate.