Well, here we are. This is probably the number one topic that keeps people from mastering Japanese. My reading ability is far from native level, but I have achieved more than I ever thought possible in this area and will share what’s worked for me. Let’s dive in…

Kanji Basics

As you all know, I’m sure, kanji were adapted from the Chinese writing system around the 5th century AD. During the 9th century, simplified versions of select kanji were adapted to represent phonetic sounds and came to evolve into the hiragana we know and love today.

On-yomi and Kun-yomi

One of the devilish aspects of learning kanji is that each one has multiple ways to pronounce it, so unlike kana, you can’t just see a new word and know how to say it. Kanji have both on-yomi (音読み) and kun-yomi (訓読み) readings and they tend to be used in different settings.

On-yomi refers to the Chinese-derived readings of kanji. These readings were borrowed from the Chinese language and have retained their original pronunciation. These are typically used when kanji appear in compound words or as part of a larger word.

Kun-yomi refers to the native Japanese readings of kanji. These readings are based on the original Japanese pronunciation and are used when kanji appear as standalone characters or at the beginning of a word.

For example, when used standalone, 山 is pronounced やま, meaning “mountain.” This is the kun-yomi reading. But when used in a compound like 富士山 (the name of Mount Fuji), it’s pronounced using the on-yomi: さん.

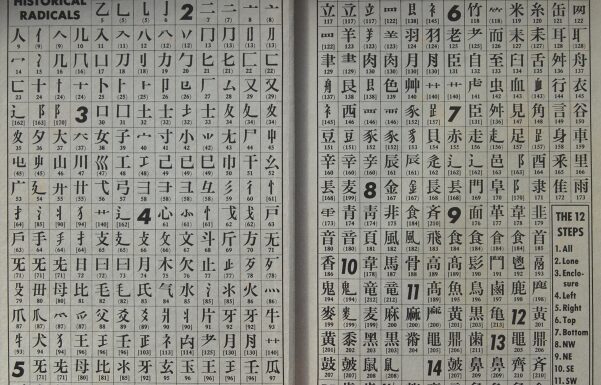

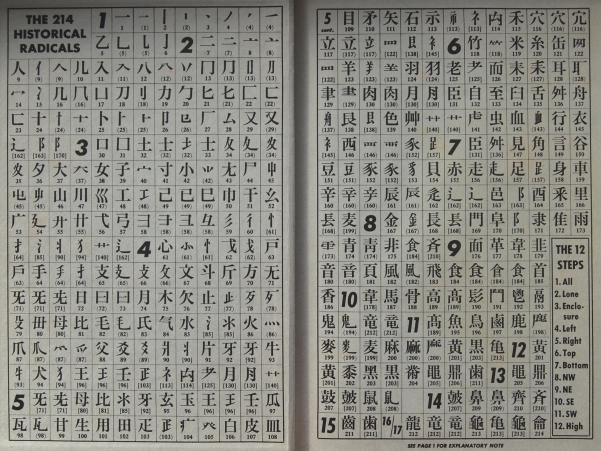

Radicals

When you look closely, you’ll see that with few exceptions, even the most complex characters are composed of smaller building blocks known as “radicals” (部首 [ぶしゅ]), which can help impart clues about the meaning, pronunciation, or semantic category of a kanji character.

How NOT To Learn Kanji

Japanese children typically learn kanji over a number of years via a systematic curriculum that assigns specific set of kanji to learn each year (i.e. 80 in first grade, 160 in second grade, etc. totaling 1006 by sixth grade), and they are learned largely by rote memorization, practice and regular assessments. I tried this approach early on, based on the recommendation of a Japanese friend, and it was painfully ineffective for me. Fun fact: 生 has six different on-yomi – don’t forget any of them during the quiz! 😒 Surely, there is a better way…

Enter James Heisig

James Heisig was sent to Japan in the early 1960s to study and engage with the local culture and language as part of a religious mission. While in Japan, Heisig became fascinated with the Japanese language and its writing system, particularly kanji. Recognizing the challenges that learners faced when trying to memorize and understand thousands of kanji characters, he developed the mnemonic-based approach outlined in his book series, “Remembering The Kanji” (RTK).

His method focuses on breaking down kanji characters into smaller components he called “primitives.” Each primitive is associated with a unique story or mnemonic, and given a keyword which helps learners remember the meaning and shape of the character. Heisig’s focus in Volume One is to assign a principle meaning to each kanji.

Since its initial publication in 1977, “Remembering The Kanji, Vol. 1” (there are three) has become the de facto standard approach for learning kanji efficiently.

Tofugu.com’s WaniKani takes the same approach and offers their version as a webapp. Disclaimer: I hear it’s quite popular, but never tried it personally.

For Example…

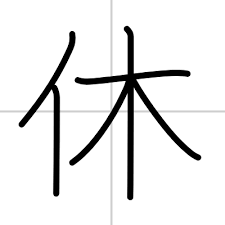

Consider the kanji 休, which has the core meaning of “rest.” Notice the two distinct parts: two strokes on the left that look like the katakana イand as a radical carries the meaning of “person,” and four strokes on the right that looks a bit like a “tree,” which is what that kanji means on its own.

As a mnemonic device, rather than “person,” let’s imagine a very specific person: those two strokes kinda-sorta look like a capital T with the top stroke tilted, so whenever you see that “person” radical, visualize Mr. T from “The A-Team.” This will stick in your brain better than generic “person” will. Now imagine MR. T leaning against a TREE taking a REST. You will likely never, ever forget the basic meaning of the kanji 休.

Putting It All Together

Start with Heisig’s book (or Wanikani) and learn the keywords/meanings for all the radicals and all the kanji. I started with a publicly available Anki deck, and modifed it to include my own mnemonic stories and, for any but the simplest kanji, a small sample of vocabulary words that include that kanji. I set up Anki to only introduce 15 or so new cards every day, as they pile up quickly.

Once you have memorized the meaning of all the kanji, when you go to learn a new vocabulary word, creatively associate the kanji’s keyword with the word’s definition, if they aren’t already the same. For Kanji compounds, you can make up a little story using the keywords, e.g. 妄想 (meaning “delusion, wild idea, fantasy”) is built from kanji with keywords “delusion” and “concept,” respectively.

In contrast to academic methods, I suggest that you do not try to memorize all the on-yomi and kun-yomi for a kanji at once. Rather, learn them organically by exposure and repetition. While kanji have multiple readings, the frequency of each reading is rarely distributed evenly, so you’ll start to recognize the most common ones for a given character. Over time, you’ll be able to form a pretty good guess on both the meaning and pronunciation of new kanji compounds.

Finally, get massive amounts of input and review via repeated exposure. Read the same things over and over again until you can’t take it any more. Start with children’s books, if you can stand them, then move on to materials more suited to your interests and personality. Above all, try to have fun with it. You’re going to be spending a lot of time learning kanji, you may as well try to enjoy it.

Resources

Beyond Heisig’s book, here are a couple of useful sites:

- https://kanji.koohii.com/ This is a one-stop shop for the RTK method that includes SRS functionality. I liked it as a source for mnemonic stories, as you can browse the characters and see what other people came up with. If I found mnemonics I liked, I’d just paste them into my Anki deck and save the trouble of creating my own.

- https://readthekanji.com This is a nice site for learning vocabulary using the kanji in context. It provides you complete sentences with the target word highlighted, you enter the reading, and it tracks your progress. You can decide what’s presented to you based on JLPT levels (N5-N1). It also has settings for hiragana and katakana. This is another resource I found useful enough that I bought a lifetime membership.

- https://tadoku.org/japanese/en/free-books-en/ This site offers a selection of free graded readers, many with accompanying audio. Obviously at the lowest levels, the stories are not particularly compelling, but you have to start somewhere.