The Forgetting Curve

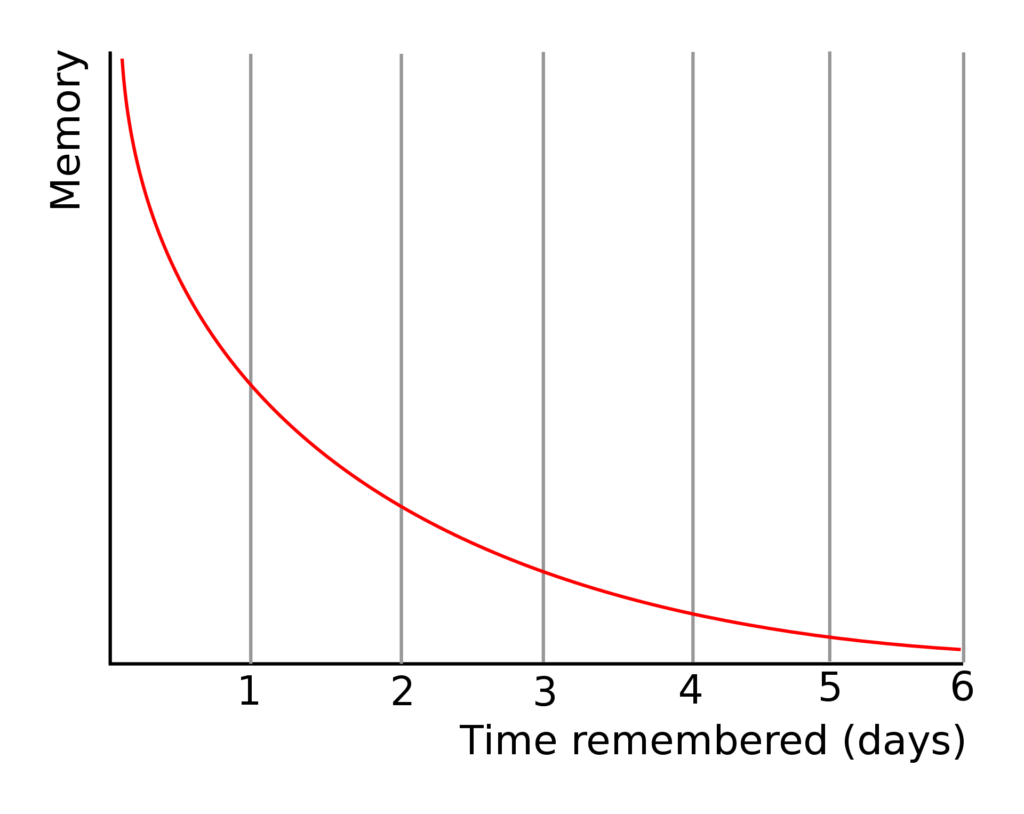

Hermann Ebbinghaus was a German psychologist who conducted pioneering research on memory and learning back in the late 19th century. He named one of his discoveries “the forgetting curve,” and it represents the pattern of how information is forgotten over time if it is not actively reviewed or rehearsed.

Key points of Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve as relates to we humble language learners:

- Rapid Initial Forgetting: Ebbinghaus found that when we learn something new, we tend to forget a significant portion of it shortly after learning it. The most significant drop in memory retention occurs within the first hour or so after learning.

- Exponential Decay: Ebbinghaus discovered that forgetting follows an exponential decay curve. This means that memory loss is most pronounced in the early stages but gradually levels off over time. In other words, you forget most of what you’re going to forget relatively quickly.

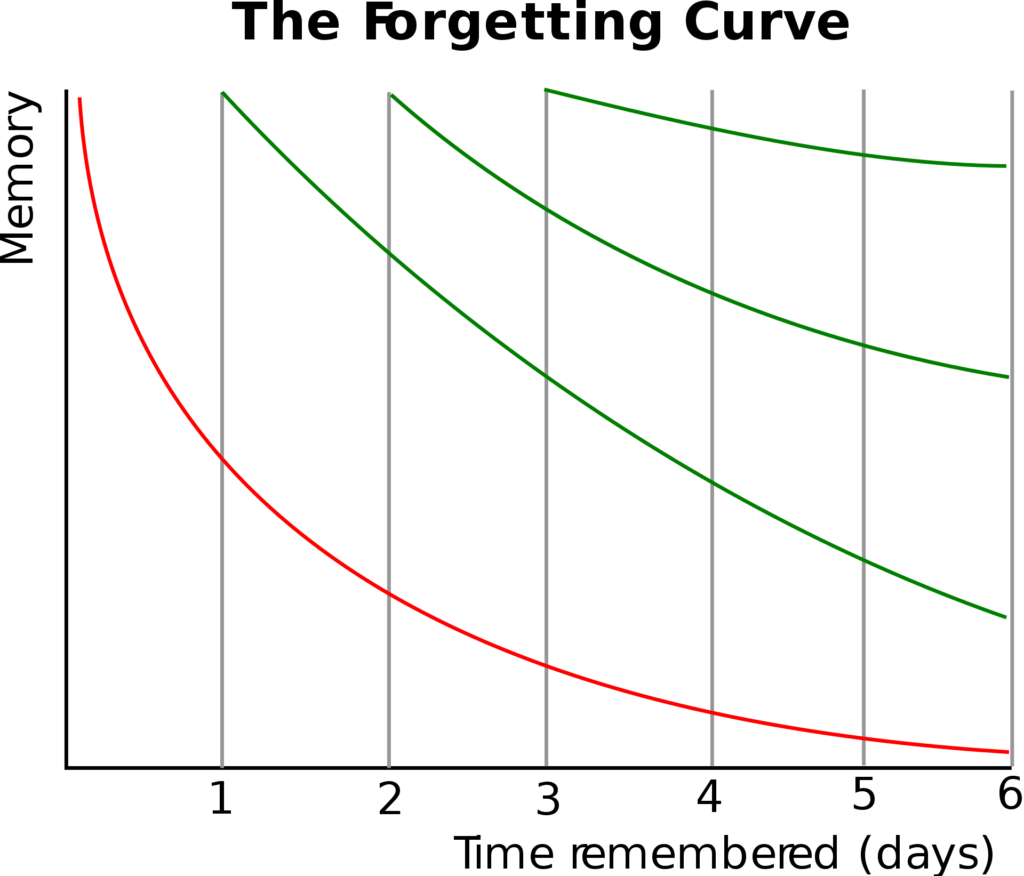

- Spacing Effect: One of the important insights from Ebbinghaus’ work is that the spacing of reviews or repetitions plays a crucial role in memory retention. If you review or revisit the material at increasingly spaced intervals, you can counteract the rapid forgetting and improve long-term retention.

This spacing effect is where the magic happens. Ebbinghaus’ research indicates that with each successful recall, the forgetting curve is ‘reset’ and more importantly, the decay rate of forgetting changes such that you forget that information more slowly than when you last saw it.

For our purposes, the main takeaways are (a) time spent reviewing information we already know well is time wasted; (b) optimal spacing has us reviewing items just before we’re about to forget them.

Spaced Repetition Systems

Spaced Repetition Systems (SRS) are all the rage for good reason: they work. An SRS provides us a way to organize bits of information we want to remember into decks of “virtual flashcards” and then uses an algorithm and feedback from us to determine when each item should be reviewed next.

In simplest terms, an SRS quizzes us about each card that is due and if we get it wrong, it shows that same card to us again very soon; if we get it right, we indicate how difficult is was for us and the algorithm adjusts how long until we see that card again based on the answer and on our history with that card.

SRS Apps

There are many, many SRS apps available and most of the Japanese dictionary apps and readers I use have such functionality baked in, as well.

Anki (暗記, Japanese for “memorization; learning something by heart”) is probably the most well-known and it’s the one I’ve used the most. Is is very full-featured: you can customize almost every aspect of the appearance, the material that appears on the front and back of your cards, even the parameters governing the algorithm if you dare, but that flexibility comes at a cost: there can be a steep learning curve to using the app if you want to exploit all of it’s capabilities, but there are tons of tutorials and such on the interwebs. One popular aspect is that there are lots of pre-made decks available and you can easily download and import one of those to get started.

Other popular apps include Memrise (created by Grandmaster of Memory Ed Cooke), IDoRecall (favorite of noted learning expert Barbara Oakley), and Flashcards Deluxe (preferred by polyglot Olly Richards), among many others. I haven’t used any of these personally, but I respect all the people recommending them, so see which suits you.

Best Practices

Consistency Like most other aspects of learning a language, consistency is far more important than intensity. For best results you’ll want to review your cards daily.

Deck Quality As I mentioned, many pre-made decks are available, but the cards will resonate with you more and be stickier in your memory if you make them yourself, using the cues and context that mean the most to you.

Context Sentences, not words. Individual words or phrases in isolation are far less memorable than if you present them in their natural context, in sentences or at least sizeable sentence fragments. You can also add pictures, your own notes, mnemonics you’ve created, anything that helps your strengthen the neural connections being formed while you review. Pro tip: even when I’m first learning a word, I often just put the word into Google image search to see what comes up.

Cloze Deletions These are a special type of card in which one or more words is replaced by “[…]” and your job during recall is to remember what does there. These types of card are especially good for learning your particles in Japanese. For example, you might have a card with 「東京 […] 住んでいます。」as the prompt. Which particle goes there, hmmmm?

Be Selective Don’t put every word or phrase you come across in a deck as it will rapidly become overwhelming.

The Dark Side

There are some downsides to SRS and I’ve experienced them all. Be cautious about…

- Time Suck. While I implore you to make your own flash cards, making good ones takes time. And if you’re trying to include too many items, you’ll find you spend all your study time making cards, not actually studying those cards.

- Backlog Explosion. Most SRS apps will feed you some configurable number of new cards each day, interspersed with cards that are due from previous reviews. This can quickly compound into a shockingly large number. And never, ever, ever miss a day because all those cards just roll over into the next day and now your backlog is twice as large.

- Dread. Particularly when the backlog gets too large, it is really demotivating knowing that when you open you SRS app, you’re going to be doing nothing but reviewing old cards for an uncomfortable amount of time. Speaking for myself, I enjoy other parts of the language learning process far more than clicking through decks of flash cards.

How I Roll

When I started studying seriously, I used Anki all the time and eventually, like many of my polyglot friends, burned out on it. These days, I don’t really use an SRS, I just rely on reviewing my study material often and looking words up when I need to. I have a large enough web of Japanese language connections in my brain finally that associating a new word or phrase into it happens pretty quickly even without using an SRS.

There are still occasions when a particular item doesn’t stick easily and in extreme cases, I will add it into an SRS after (a) failing to recall after reading it many times; and (b) deciding that it could be useful in my future (e.g. something I’ve seen often in multiple sources or just a cool word that I like and want to know).

Just to put a fine point on this selectivity, my primary reading source at the moment is a great site/app called SatoriReader.com and over the past several months, I’ve added a total of eight words into its built-in SRS. And once I feel I know a word, I’ll just delete the card and stop reviewing it entirely.

One last thing: An SRS is not just for vocab only. You can also test yourself on grammar rules, history, anything. As long as you can formulate your question onto a card, the sky is the limit.