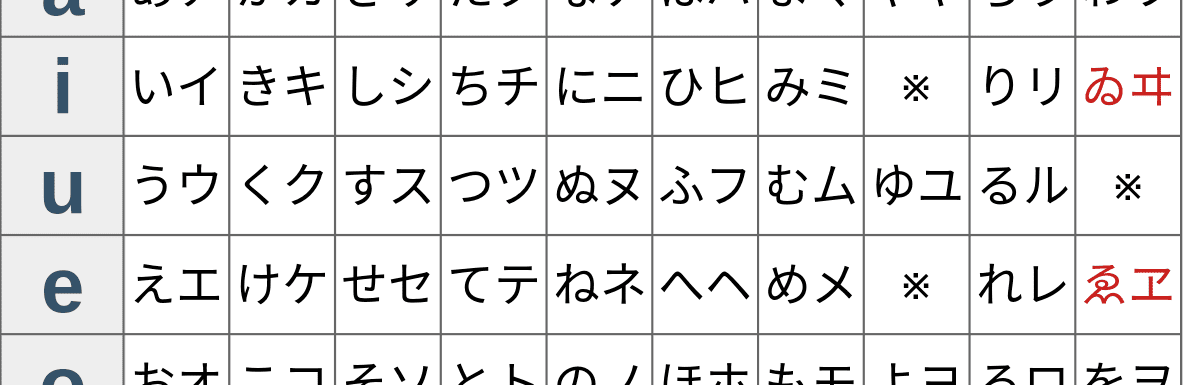

Japanese has three different primary writing systems (four if you count their use of the Roman alphabet, known as “rōmaji”): hiragana, katakana and kanji. Do yourself a favor and learn hiragana and katakana as quickly as possible.

Hiragana and katakana are syllabaries collectively referred to as “kana” in which each character represents a single, specific sound; kanji are Japan’s adaption of the Chinese writing system in which characters are used and combined to represent concepts. The Ministry of Education dictates that one needs to know 2,136 kanji characters to be considered literate.

Hiragana are used for writing native Japanese words as well as for things like verb declensions. For example, the verb “to eat”, 食べる (pronounced “taberu” in romaji), is written using a kanji character plus two hiragana characters that convey the final sound. If you wished to write this in the casual past tense form “tabeta”, it would be 食べた.

Katakana are primarily used for transliterating foreign words like “radio” or “smartphone”, e.g. ラジオ, スマホ (“rajio” and “sumaho” in rōmaji).

Kanji convey both sound and meaning and are the most complex of the written forms, as some take over 30 strokes to write and they can have multiple readings, based on how they’re used. 生, for example, can be read twelve different ways (more if you count usage in proper names).

A fourth writing system, known as rōmaji (ローマ字, literally, “Roman letters”), is simply a Romanization of Japanese in which Latin script is used as a phonetic representation of Japanese words. This is quite common in textbooks targeted toward beginners. For example, “thank you” might be encoded as “arigatou gozaimasu.” Together with a simple table showing how one should pronounce each letter, digraph or diphthong (e.g. ‘a’ sounds like the ‘a’ in ‘father’), it’s the fastest path for newbies to start reading their lessons.

Unfortunately, depending on rōmaji causes more problems than it solves. For one thing, if you should make it to Japan and want to read anything besides your beginner textbook, watch television with Japanese subtitles (more on this later), take more advanced courses, etc., you won’t find much rōmaji. Moreover, if you learn to read kana, you’ll be less likely to project your “native” sounds onto the Roman letters so you’ll learn to speak and understand correct pronunciation. I strongly recommend at a minimum learning the hiragana and katakana as quickly as possible.

How quickly? I have to laugh because occasionally I see comments on internet forums from people who’ve been studying kana for months and that, candidly, is ludicrous. When I started studying Russian in college, I had to learn the Cyrillic alphabet: 32 letters, upper- and lower-case, block-printed and script — basically 128 characters, granted many similarities. We were given one day to learn block-printed and one additional day to learn script. After that, everything was in Cyrillic.

Hiragana and katakana each have fewer than 50 characters and I would argue that with the help of the book below (linked to Amazon), it shouldn’t take more than a day or two to learn each. My own experience reflects this: using the mnemonic methods spelled out by Heisig, I learned hiragana in one day and katakana the next and have never forgotten them, even over some multi-year periods during which I did nothing with Japanese.

Note: after this, you will see very little rōmaji here, so please do yourselves a favor if you’re serious about learning Japanese and learn the kana.